This week, Americans celebrated Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Learning and reflecting about race is a great way to spend MLK Day; however, 2020’s racial unrest (if not America’s entire racial history) has proven that a more consistent national effort is necessary to achieve racial equity and equality. Unfortunately, it’s easy for a lot of West Virginians to ignore racial problems facing the country and their individual communities. West Virginia is often cast off as irrefutably white, which diminishes the past and present Black existence in the state. I believe that it also helps white West Virginians distance themselves from racial conflicts, making it seem like it’s not their problem.

“Everybody can be great…because anybody can serve. You don’t have to have a college degree to serve. You don’t have to make your subject and verb agree to serve. You only need a heart full of grace. A soul generated by love.” – Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Black history in Appalachia has been researched by a number of scholars and folklorists, beginning with William Turner and Edward Cabbell’s 1985 book, Blacks in Appalachia, which undermined the image of Appalachia as solely white. Over 20 years ago, the experience of Black Appalachians was also validated by the term and concept of Affrilachia. Frank X Walker coined the term to create a space and identity for Black Appalachians, who had been consistently left out of Appalachia’s narrative. Frank X Walker is a University of Kentucky English Professor, Kentucky’s first Black poet laureate, and a native of Danville, Kentucky. He published a poem entitled “Affrilachia” within a poetry collection of the same name. The poem begins with friction between white and Black Appalachians, and then cycles through cultural phenomena that bind Appalachians. He states, “that being ‘colored’ and all is generally lost somewhere” in the stories told of Appalachia. The poem helped me better understand what it would feel like to be both strongly connected to a place and simultaneously rejected by it. I first read the collection last year, and upon rereading it this week, I’m again overwhelmed by its poignancy. I recognized familiar parts of life in Appalachia and glimpsed a different experience of living here. It’s thought provoking, heart wrenching, funny, and truthful.

Affrilachia by: Frank X Walker for Gurney and Anne thoroughbred racing and hee haw are burdensome images for Kentucky sons venturing beyond the mason-dixon anywhere in Appalachia is about as far as you could get from our house in the projects yet a mutual appreciation for fresh greens and cornbread an almost heroic notion of family and porches makes us kinfolk somehow but having never ridden bareback or sidesaddle and being inexperienced at cutting hanging or chewing tobacco yet still feeling complete and proud to say that some of the bluegrass is black enough to know that being ‘colored’ and all is generally lost somewhere between the dukes of hazard and the beverly hillbillies but if you think makin‘ shine from corn is as hard as Kentucky coal imagine being an Affrilachian poet

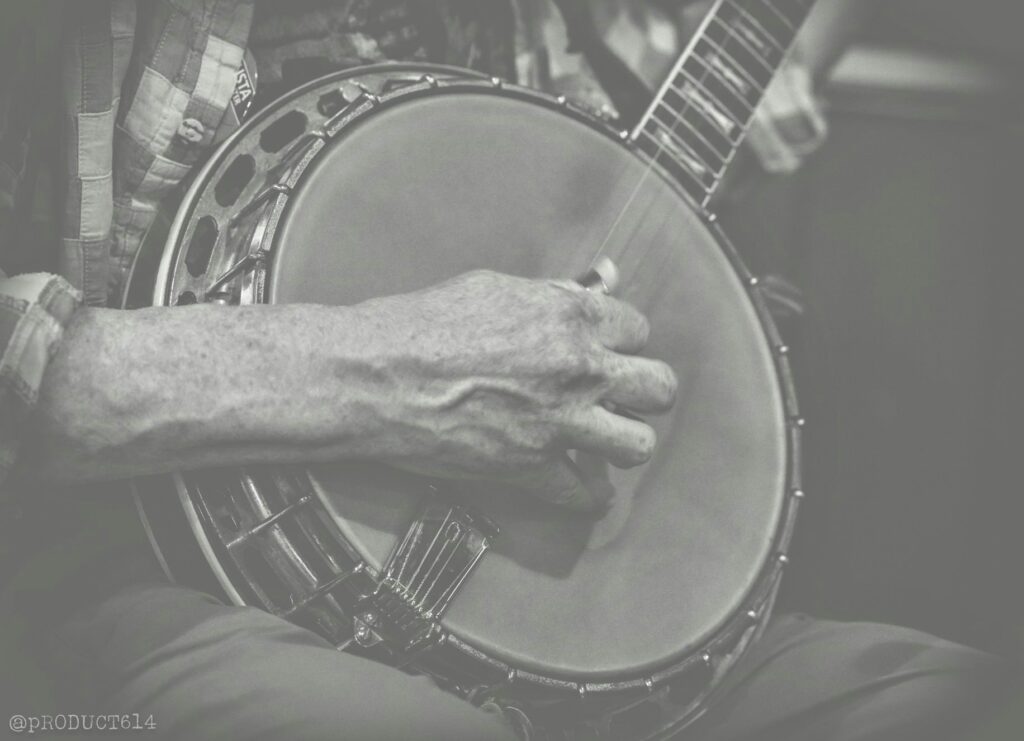

I think it’s important for white Appalachians to think about why it was necessary to create the concept of Affrilachia. As my position at Augusta primarily involves listening to archival tapes of Appalachian music, I’ve been looking into the exclusion of Black people as it relates to music specifically. I’ve tried to question how the musical traditions came to be, who is being credited with the music, and who is left out of the narrative. Although Black people have influenced Appalachian music traditions, their contributions went unacknowledged for generations and are still often excluded from mainstream depictions of Appalachia.

Collectors of Appalachian music and folklore have helped write the history of Appalachia by filling archives with the evidence scholars use. The archival contributions of folk collectors are still valuable; however, it’s important to question what’s missing from these records. Folk collectors helped proliferate the notion of white racial purity in Appalachia by excluding Black people from their research. Media portrayals of Appalachia, like Deliverance, have also enforced notions of homogeneity in popular culture.

In more recent years, scholars have examined collections more critically, recognized the exclusion of Black people from notable collections like that of Cecil Sharp, and rewritten the history of old-time music to acknowledge both the exclusion and influence of Black musicians. Additionally, Black old-time musicians and festivals, like the Carolina Chocolate Drops and the Affrolachian On-Time Music Gathering, have brought attention to Black contributions to the genre and fostered a vibrant community of Black old-time musicians.

In many of Augusta’s oral histories, white musicians cited Black musicians among their influences and described their presence in the community. Oftentimes, Gerry Milnes specifically asked about certain Black musicians or the Black communities in different parts of West Virginia. These tapes (from the 1980s-90s) have shown me that many of the people within the genre did recognize the Black influence on old-time music, even if the mainstream image of Appalachian music was and is oftentimes white.

Over the course of the 20th and 21st centuries, folk collectors, scholars, and musicians have worked to recognize and uplift modern Black musicians and historic Black influences. Despite the great progress in the old-time community, the racial crisis of 2020 has shown us that there is still work to do in every field. Affrilachia was and is necessary because in the words of Dr. King, “The tendency to ignore the Negro’s contributions to American life and strip him of his personhood, is as old as the earliest history books and as contemporary as the morning’s newspaper.” The work of achieving racial justice shouldn’t be shouldered only by Affrilachians but also by white Appalachians who have a role to play in creating an inclusive future for Appalachia and old-time music.

Walker, Frank X., “Affrilachia.” Affrilachia, Old Cove Press, 2000, pg. 92-93.

Photo by Chuck Johnson