Just in time for thanksgiving, Ron Howard’s Hillbilly Elegy was released on Netflix. Three week earlier, critics began publishing an onslaught of scathing reviews of the film. Overall, critics claimed that the film perpetuated stereotypes about Appalachia and the Rust Belt and was generally a subpar film in terms of entertainment. Although the film stands on its own, it is difficult to discuss it without talking about its source material: J.D. Vance’s memoir, Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis. The book was released in 2016 and stirred up a lot of controversy. It became caught up in maelstrom of the election, curiously praised across the political spectrum. The politicization of the book was driven in part by J.D.’s appearances and commentary on various news stations. Despite its mainstream approval, many scholars and residents of Appalachia were outraged by the tail end of the title. The stereotyping in the book and the prescriptive nature of Vance’s attempt to speak for an entire culture elicited the publication of many articles and an anthology, Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy, in response.

I’ve read the book twice now—during my freshman year of college (2016-2017) and this fall before the movie premiered. I think the book enables the reader’s biases about class, Appalachia, and the American Dream to shine through because there’s something for people across the political spectrum to cling to in fury or compassion. For that reason, I want to express where I’m coming from when I read the book and watched the film.

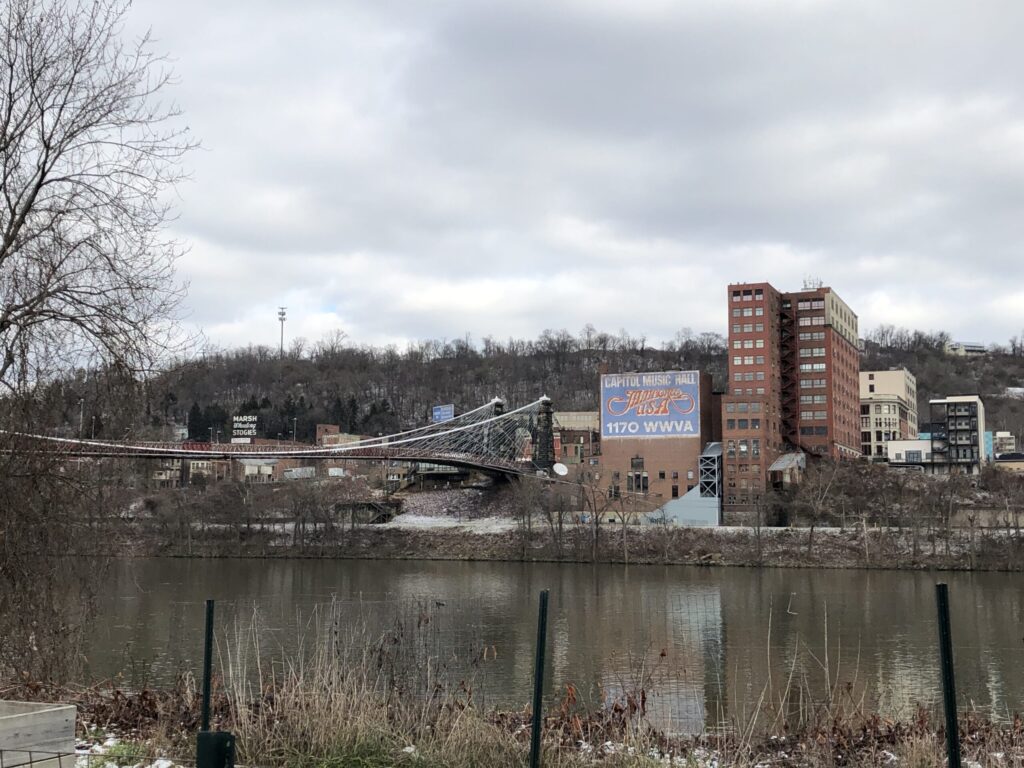

Both times I read it, I found aspects of Vance’s life and family relatable. Like Vance, I’m the grandchild of an Ohio plant worker, whose factory was shedding jobs and benefits throughout my childhood before shuttering completely; I grew up in Wheeling, which occupies both Appalachia and the Rust Belt; I regularly had family meals at Cracker Barrel; and I left the region to attend college (my grandpa would call Vance’s alma mater the Emory of the North). The first time I read it, I was thrilled to see my family’s loyalty and fierceness reflected in mainstream literature, and I found Vance’s argument about the cultural problems in the region disagreeable but familiar. A lot of my friends’ parents, teachers, and community members shared somewhat similar beliefs about the problems facing families in economically down-trodden areas. In retrospect, I think it was much easier to breeze past Vance’s sociological arguments because I had just left Appalachia for Atlanta. At the time, I didn’t think I would return.

When I reread the book, I felt the same connection to Vance’s grandparents, but now back in West Virginia, I was more critical of and offended by his attempt to project his experience onto my life and the entire region. Although his opinions weren’t new to me, seeing J.D.’s rise in the political sphere has shown me how much weight his words carried. While the film is intended to be the family’s story, the memoir reaches to speak for a culture, which seems like an impossible feat to me. Working at Augusta Heritage has also opened my eyes to fascinating aspects of Appalachian culture and history that defy stereotypes and are absent from the Hillbilly Elegy image of Appalachia. Vance’s vision of Appalachia is limited to his own experience, and perhaps the biggest problem with the success of his book is that readers outside Appalachia may only read his narrative about the region.

Although the response to the film has been much less favorable than that of the book, the film is contributing to the media representations of Appalachia and the Rust Belt, which can shape the perceptions of the regions. With the shadow of Deliverance still looming over Appalachia, it’s hard to deny that media representations—even when inaccurate—have an impact. In anticipation of the movie’s release, I interviewed Molly Hughes, a West Virginia native and the film’s production designer, to better understand the approach and intentions of the film. This interview and my thoughts after watching the film have each been posted to this blog separately. I hope that the interview can offer insight into the film’s production and that my response will provide fresh ways to think about the images and concepts brought up by the film. Additionally, I recognize that the book and film can trigger intense feelings and biases, and I hope that this post will provide context for my response to it.

With J.D. Vance’s nomination as vice president on the Trump ticket, I thought I would learn a bit more about him. I have not read his book but did watch the movie, “Hillbilly Elegy”. Thus, I cannot speak to what he says about Appalachia in the book. However, the movie mirrored what I saw in my own small town in Indiana located an hour away from Middletown. Growing up in the 60’s & 70’s my town like many across Ohio & Indiana were, for the most part, picture-perfect examples of the best of life in small town America. Jobs were plentiful due to the factories that manufactured parts for automobiles, appliances or contributed other necessary items for goods manufactured in America. During the 80’s as factory after factory closed, many of my friends and our parents lost job after job with no viable job skills and little money to invest in obtaining an employable skill. My friends weren’t lazy but were stuck and didn’t know how to climb out of a hole created by factories closing and moving to regions where labor was cheaper and unions didn’t exist to protect the worker. This created the atmosphere in which J.D. and your generation have grown up. Those who did not experience the sad development of the

“Rust Belt” can criticize J.D.’s portrayal of life in Middletown, Ohio but the movie displayed the depressingly real aspects that resonate with many of us who experienced it and many who are still living through it.